The left-wing woke capture of the West's institutions, quantified

After being driven out of medical school early this year, I was traumatized.

It came at the tail end of me bursting onto the scene on Twitter when I realized that I had been wrong about COVID-19. Up to that point, I had been a debunker of misinformation, mostly in nutrition, then in health more broadly. I did it because the obesity epidemic was such an important public health problem. But there was so much misinformation around about nutrition. If nobody could agree about what the science actually said about nutrition, then how could we create policy to solve the obesity epidemic?

So I became a nutrition debunker, and I spent thousands upon thousands of hours over the years refining my techniques. Debunking popular diets was unpopular—but necessary. So I got really, really good at making boring, unpopular positions more exciting and appealing. I worked endlessly at it, making videos, articles, podcasts, and constantly experimenting with my format and image.

By chance, I happened to tweet about Covid. Until that point, I had strongly supported most of the measures used to combat the virus. If anything, I thought that those measures should be stronger. I was in favor of police intervention to keep people inside their homes during lockdowns.

But I began to slowly change my mind. I voiced that change strongly at the end of 2022. And then, I thought I would try to apply some of the skills and techniques that I developed above to commenting on COVID-19 policy.

So, imagine getting really good at making boring things interesting and unpopular positions appealing. And then suddenly dropping in on a topic that many people thought was interesting and popular.

Uh oh.

I was invited to write an op-ed at Newsweek, and I did: https://www.newsweek.com/its-time-scientific-community-admit-we-were-wrong-about-coivd-it-cost-lives-opinion-1776630

I didn’t expect for it to be one of the biggest op-eds published in 2023. I was just writing my opinion, drawing mainly from my own personal experience of strongly defending the COVID-19 policy establishment, and fusing that understanding with the work of Batya Ungar-Sargon and Jay Bhattacharya. The piece had some banger sentences, sure, but it was pretty poorly organized. My ideas were still very raw and impressionistic.

I had done my best version of a written Monet, and I had crossed my fingers. I submitted the piece, and my editor texted me. It’s published! For the first hour, I was frozen in bed, in a state of terror but doing my best not to send my editor a message telling her to unpublish it.

It was one of the biggest articles trending on Newsweek in years.

From then on, everything I tweeted began to go viral. My online friends, almost all in academia, told me to stop. Among them included some of the most influential voices in medicine. I remember some of those conversations like it was yesterday.

In response, I went on Tucker Carlson. I mean, naturally. Because what one does when your friends at some of the highest levels of academia tell you to stop or else you will destroy your career due to the politics of the topic? What one does at that point is definitely to go on Tucker Carlson.

To be perfectly transparent here, I did it in part because my parents wanted me to. They are serious Trumpers and MAGA enthusiasts. Up until this point, I had been a lifelong Democrat, even during my adolescence and early adulthood, a communist. The pandemic had therefore split us apart.

They, like many conservatives, felt validated by my coming around to their view. And I explained to my dad that I had once turned down a Joe Rogan interview a few years back and regretted it. He said to me: “You will regret this one too then.” He and my mother encouraged me. They were so proud and excited for me.

I take responsibility for my actions, and I am not ashamed of them. I might have done differently today because of what the outcome was. I don’t feel that my actions were wrong. But that was the context.

What followed was the beginning of a nightmare. I was unfollowed by the most influential accounts on #MedTwitter. Then I began to be viciously attacked by these same accounts. They repeatedly tagged my medical school and demanded my expulsion.

These attacks were personal and emotional. And they were aimed at my credibility and my status as a student rather than my scientific claims.

Then followed belligerent, posturing demands for “debate.” Those who challenged me were influencers who were not well-trained scientifically, not particularly intelligent, and their attacks on others’ ideas mainly used derision, mockery, and appeals to authority. One of these individuals I did try to set up a debate with. However, he was so derisive and aggressive in his text messages that I told him his way of communicating caused me anxiety. I also said that he did not seem to be scientifically serious, and I cancelled the debate. He responded by publicly tweeting I cancelled the debate because I had mental health problems. Then he signed me up for hundreds of robocall services, and my phone became unusable for two weeks, belying his expressed concern for my alleged mental state.

Some did attempt to debunk some of my tweets, but these were by incompetents without training who appealed to other incompetents without training. I did not respond to these “debunkings”.

Instead I turned inward. How could it be that the “bad guys”, i.e. those who were outside of academia and were frequently accused of spreading misinformation (in fact people I had debunked in other areas), could be the ones who were right? And how could the “good guys”, i.e. my friends in academia, be wrong? I spent a lot of time trying to figure out where I was wrong and where I was right.

I came to understand that virtually all of COVID-19 policy had been infected by ideology—in a very similar way as various diet cults are. For these cults, every question of nutrition science comes to be resolved by reference to the preferred dietary ideology, so that science becomes a mere rationalization mechanism to justify previous beliefs.

So too was it with mainstream COVID-19 science and policy. But where exactly did that ideology come from?

When I started medical school again, I faced a level of bullying unlike any that I have experienced in my life, driving me out

Trying to make sense of what I experienced, I also now had the free time to try to answer my question: where did the ideology come from? Partly, I believe, it came from the ideological capture of the white-collar professions.

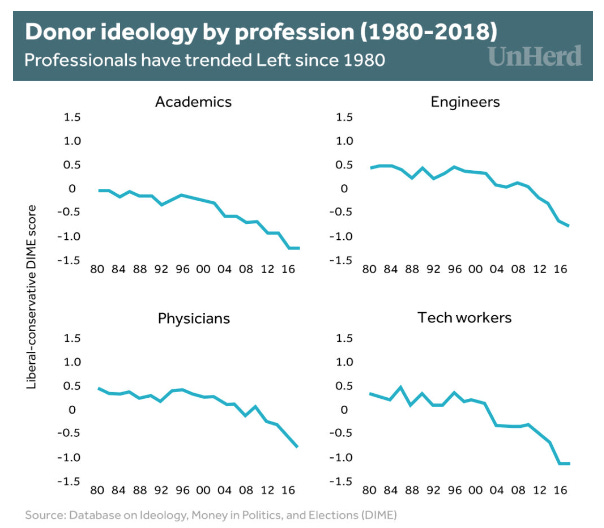

In the course of my investigations, I generated this graph.

Now, the fine print about methodology before diving into more substantial matters: I generated these figures using Adam Bonica's DIME dataset at Stanford (link). They were generated by plotting the donor scores of physicians who had made political contributions during the respective years. Such measures have been shown to strongly correlate with the ideology of donors and thus serve as a proxy for the profession's ideological leaning, especially in recent years, where more than 10% of physicians have made such political contributions. These data, especially those over the past few years, have not been published until now.

The code used to analyze the database and produce the figures is on Github, link.

There are two major interpretations of these graphs. The first is that they represent an authentic change in the political alignments of people in each of these professions. The other is that, because these figures are readily available from the Federal Election Commission, conservatives are increasingly wary of being seen to be publicly making contributions to Republicans.

Either way, it’s a scary situation.

Here is another way to plot some of these findings:

Two interesting analyses have been published to explain these figures. To summarize:

The trend in the data that I found are present in other datasets of diverse methodologies;

These trends are not isolated to the United States but, rather, are found internationally;

Left-wing views dominate among students, with virtually no conservatives among those at elite institutions;

This trend has been gradual but accelerated in 2008 (Obama years) and then sharply swerved in 2016 and 2020;

The more manual labor professions have been somewhat resistant to this trend, but not entirely.

I link these two articles now for your perusal.

But before visiting these links, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and supporting my work.

Links:

My article in the New York Post talks about the same phenomenon from the perspective, specifically, of medicine, here.

Cheers.

people who work on laptops are left, people who work with their hands are on the right.

This is setting-up an ironic form of class warfare where the right is the working class... weird.

You are so right on all of the points. Medicine is in the Wilderness. I say that as someone who graduated from med school in 1975. There is no critical thinking, no courage, no ethics. All is ideology. Unfortunately, nothing new. See: https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/history/articles/fernandes-doctors-who-became-nazis For some reason, our profession is prone to ideological capture. The root cause needs exploration and exposure. We probably use the wrong criteria for entry into, and advancement in, our profession.